An American tourist was on holiday in Ireland one time, and he happened to find himself sort of lost in someplace in east County Cavan. He was driving around back roads for a good while and eventually saw some old fella leaning against a gate, so he pulled over and said “Howdy sir, would you mind awfully telling me how to get to Dublin city? I’d be much obliged”. So the auld fella took off his cap and scratched his head, and in a fairly slow Cavan drawl says “Well I can, but if I was you I wouldn’t start from here”.

Where do the British&Irish Lions start? Thousands of words have been written, interviews conducted and studies done about what makes the New Zealand rugby team different from everyone else. I’ve even written about them before myself Talent Development – from New Zealand to Kilkenny. On Saturday New Zealand demolished the Lions in the 1st Test. The Lions were outplayed from start to finish. When New Zealand had possession you felt the longer they held onto the ball and more phases they went through, the likelier they were to score. The Lions, well, the more they held the ball and more phases they went through, you felt they’d get turned over at ruck time or simply kick the ball away. This article will examine Saturday’s game and the difference in mindset of both sides in the context of one area, in my opinion they key area in the game of rugby today: the breakdown. Once first phase ball has been secured (and with two top quality teams like these one can assume they’ll win their fair share of lineouts and scrums), the majority of possession in a game will come from the breakdown. If a team goes through 20 phases- you can be fairly sure about 18 of those 20 will start from rucks. The ruck is where you start from.

It was noticeable on Saturday that New Zealand and the Lions had a very different approach to the ruck. The statistics show New Zealand had a much greater number of rucks, 131, winning 127 (96%). The Lions had 76 rucks, winning 72 (winning 94%). Of these 131 rucks, New Zealand created quick ruck ball 39 times, or 30% of the time. That’s an awful lot of pressure to put the Lions under. The Lions themselves managed to generate quick ball 22% of the time from their breakdowns, 17 times out of their 76 rucks. New Zealand frequently committed a player to Lions’ rucks to contest possession. The Lions rarely committed players to contest New Zealand rucks. These two facts framed the entire contest and the stats reflect this. New Zealand competed for the ball on Lions rucks 26 times of the Lions 76 rucks, 35% of the time. The Lions, on the other hand, competed at the breakdown on New Zealand ball 18 times out of New Zealand’s 131 rucks, just 14% of the time.

In possession, the two teams had differing approaches to their own rucks. New Zealand sent two or three players to clear out, these being close to the ball carrier and clearing the ball with huge aggression, speed and power, obviously aided by lack of competition from Lions players. The Lions sent (or had to send) more players to secure their own rucks. One statistic I’d love performance analysts to stop counting as a positive is “rucks hit” – New Zealand players I’m sure have low numbers on rucks hit, as when two New Zealanders go to clear a ruck, they bloody clear it. Their attitude is “why send four to half-arse clearing a ruck when we can make two do the job perfectly”; in contrast northern teams generally say the opposite: “two guys will struggle to clear that ruck unless they do it perfectly, so let’s send four to be sure”.

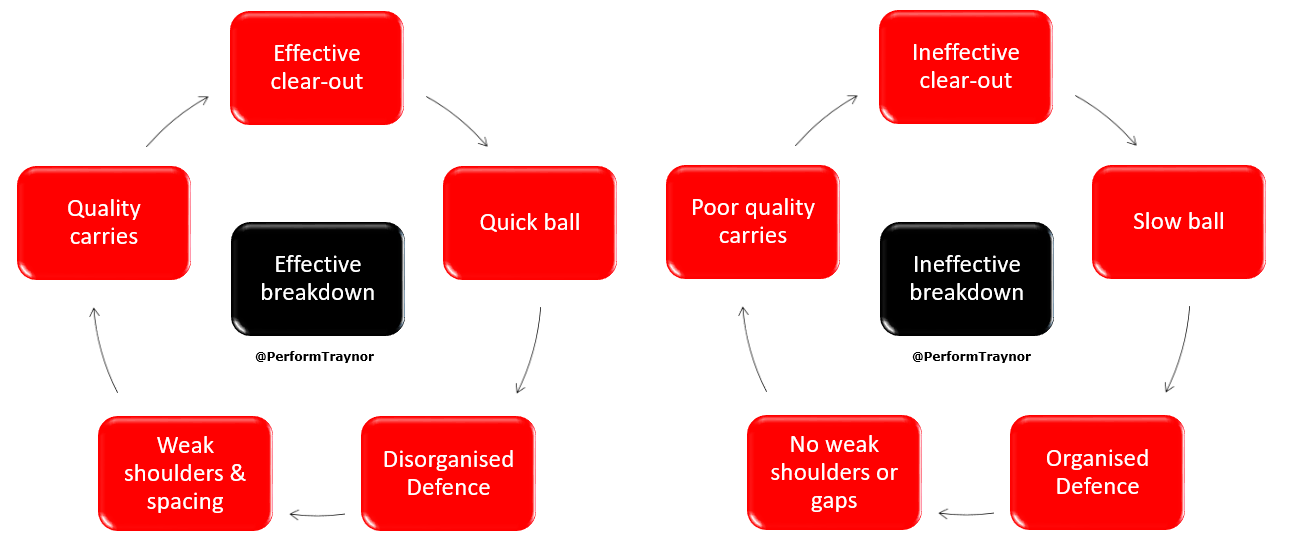

There are many differences between how northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere teams play the game. Most can’t put their finger on what makes New Zealand so different, so successful. The breakdown is certainly one clear area of difference. The impact of a ruck on attack and defence go hand-in-hand, so I’ll discuss both below. This graphic illustrates why the ruck is of such value.

Northern hemisphere teams value numbers in defence and attack over all else. Coaches in the northern hemisphere believe the overlap will come eventually, and finishing the overlap is the key to scoring tries. Conversely, in defence, preventing the opponent from gaining an overlap is the key aim. Northern hemisphere coaches believe that organised phase attack will lead to an overlap, and coaching players to identify overlaps and exploit those overlaps with tries is how you score. Players are conditioned to value creating a 2v1, 3v2 or even a 6v5 as the best scenario they can have. Go along to any training session from under-10 all the way up to adult rugby and watch how many drills or conditioned games are played with the aim of creating/preventing the overlap. The key problem with this? Really good teams rarely give you a situation where attackers outnumber defenders, and even if they do their defensive skills are that good that they can deal with it.

Southern hemisphere teams value quick ball over all else. The attack’s job is to generate quick ball and the defence’s job is to prevent the opponent from generating quick ball. When you watch them play, attacking weak shoulders or defenders who aren’t set is their main aim. And in defence, slowing the ball long enough to allow the defence set up is what they’re after. They believe tries are scored by generating ruck ball so quick the opposing defence is disoriented, defenders make mistakes, and the opposing defensive line cannot be set up quickly enough to effectively shut down the opposition. New Zealand in particular expect the opposition defence to be organised, and very rarely expect there to be an overlap. They go through teams, rather than around them, better than anyone else. They look to create situations where they run at weak shoulders, and situations where the defender can maybe make a tackle, but never a dominant hit (which is where offloads come from). The key to all of this is quick ruck ball. Don’t get me wrong, the New Zealanders can kill you if an overlap develops, but first things first.

The breakdown is where these cultures clash. On Saturday, the Lions stood off rucks, allowing New Zealand win their own ruck ball easily, and ensuring their defensive line couldn’t be outflanked by superior numbers. New Zealand were pretty delighted with this, launching phase after phase of attacks with this super quick ball. On the other side of the ball, New Zealand went after each Lions ruck whenever possible. On occasion, New Zealand managed to win a turnover on the ground or penalty at the breakdown, but the main reason they did this was to prevent the Lions from having quick ball. Contesting the ruck slows the ball down. Slowing the ball down does two key things: makes the Lions commit extra players to the ruck which takes away players from their attack, and most importantly gives the New Zealand defence an extra second or two to set their defence and number up.

The selection of scrumhalves is a very telling example of the difference in philosophies. The New Zealand team selected Aaron Smith at 9, probably the quickest 9 in world rugby at present. The ruck ball was quick, but his passes were like a machine gun, sprayed here there and everywhere. As soon as he saw a bit of white in a ruck, the ball was gone. It hugely helped the attack gain momentum. On the Lions side, Conor Murray is far more methodical. He is selected for a range of attributes- he is a very good tackler, his box-kicks are the best in the world, he is strong around the ruck, he rarely makes mistakes. His delivery and ability to build tempo in his team’s attack is not the strongest facet of his play.

Changes for Saturday’s 2nd Test? The Lions need to up their speed of attack and to compete at ruck time in defence. So personally, I’d make a couple of changes to the side. There was a noticeable improvement in the Lions tempo when Rhys Webb came in, albeit with the game already decided. Whether the Lions decide to bring Webb in to start on Saturday depends on if they value his energy and tempo over the range of skills Murray has, and that will come down to whether they want to play a quicker game or not. Likewise, unpopular as this will make me sound as an Irishman, I’d bring in Warburton for O’Mahony, and Itoje for Kruis, both changes designed to make the Lions more competitive at ruck time. O’Mahony has been excellent on tour, but the game the Lions need to play would fit Warburton perfectly. He’s a ball poacher and turnover getter, and if they go after New Zealand he can make some huge plays. Itoje has to start. There’s no point bringing on an impact sub with the team already fighting a losing cause. Use his energy from the start.

The Lions can win the remaining two tests. I could speak further on other aspects of the game like the set piece, the kicking game, each team’s defence systems. But all of these all stem from the breakdown battle. The Lions need to focus on winning the ruck contests first and foremost. Win that battle and everything else will follow.

https://www.instagram.com/performtraynor/

https://www.facebook.com/PerformTraynor/